Fighting the Fake News Virus and Infodemic Risks

Let us begin with a pop quiz. Can you define the word, ‘infodemiology’?

According to the World Health Association (WHO), ‘infodemiology’ is the study of the flood of information about COVID-19, known as the ‘infodemic’, and how to tell the difference between reliable reports and misinformation.

Let us try another question. Is Fake News defined as:

- False information knowingly spread with an intent to deceive

- Misinformation, meaning false news spread by those who believe it to be true

- Propaganda, likely originated from a government or political source

- News with which the reader disagrees

If your answer is ‘all of these’, then you are in line with a recent survey of 100 journalists.

Clearly, we have a huge problem if a body as powerful as WHO is taking it so seriously. And, equally clearly, we have an even bigger problem when it is so difficult to pin down the exact nature and source of the Fake News threat.

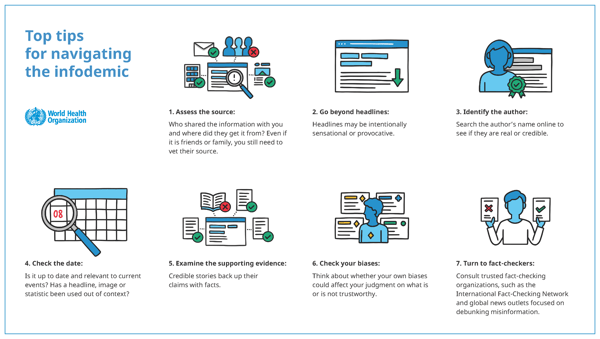

WHO created this infographic as guide to identifying misinformation or disinformation:

WHO is also working with more than 50 digital companies and social media platforms to ensure that science-based messages from official sources appear first when people search for information related to COVID-19.

To support WHO’s initiative, scientists and other health experts also are looking at how they can communicate more effectively to overcome people who are distrustful, skeptical and lacking a science education, according to the magazine of John Hopkins Medicine.

The John Hopkins magazine interviewed a resident at the hospital who has taken a sabbatical to work as a medical journalist for ABC News. The resident, Heather Kagan, had developed her own list of words not to use:

- Medical jargon such as ‘outcomes’, ‘indicators’, ‘clinical’ and ‘presenting’

- Terms like ‘comorbidity’ and ‘risk factor’ which have a specific meaning in a medical setting but can alienate a general audience

Kagan also says that she has learnt the importance of occasionally saying, “I don’t know”. This point was amplified by Joseph Ali, a lawyer by training and now an assistant professor at the School of Public Health, who observed in the article:

“Some experts have a tendency to want to fill in knowledge gaps to provide reassurance. That’s coming from a good place with good intentions. But we have to build trust, and in times when expertise is in high demand and we don’t know everything, we must carefully manage communications.”

Public health organizations, doctors, scientists and journalists are all doing what they can to combat fake news. There is also a role for public relations professionals.

In 2019 a survey found that two-thirds of PR professionals called fake news a serious threat – but only 19% thought the issue had any bearing on their work.

That Greentarget report into Fake News and the media suggested that the PR industry could not afford to be so passive and suggested that practitioners commit to a pledge to:

- Support the work of reporters and editors

- Stress ethics and transparency

- Put the audience first

- Advocate against fake news

Even John Hopkins, who as noted earlier had been actively working against the infodemic, itself had been threatened by fake news. In March, a post allegedly authored by a Johns Hopkins epidemiologist (who does not exist) went viral on social media, giving bad advice and misinformation. The communications team raced to respond to and refute the post, and worked with Snopes, a fact-checking website, to discredit the rumors.

Of course, the mainstream media carries the largest share of the responsibility for dealing with the problem of fake news and misinformation. That is a strong challenge as, arguably, no-one has suffered a greater impact from 'fake news' than the mainstream media who no longer occupies the position of trust that it once held.

Two-thirds of those 100 journalists interviewed for the report said they did not expect any government action and that it was the responsibility of reporters, editors and journalism to vet fake news.

And, by the way, in case you thought that the phenomenon of fake news was in some way related to one political party or another – that survey of journalists suggested that they do not expect anything to improve with a new administration from January 20 next year.

If anything is going to change, it is time for everyone to do what they can.

Learn how hundreds of organizations large and small are using our award-winning issue and crisis management platform, In Case of Crisis, to better prepare for and respond faster to emerging threats.